The windswept plateau and rocky cliffs of Lundy look rather barren when approaching the island from the sea, but a rich and colourful flora, adapted to life in these exposed conditions, is more obvious once on land. A walk from the Landing Bay, up the beach road, through Millcombe and then to the west side by way of the Old Lighthouse would take in many of the important plant habitats on the island.

A typical sea cliff flora of Thrift Armeria maritima, Sea Campion Silene uniflora and Sheep’s-bit Jasione montana is found on the exposed sidelands of the island, especially around the Battery and towards the north end. At the south end, and on Rat Island Kidney Vetch Anthyllis vulneraria and Common Sorrel Rumex acetosa are more frequent, and Wild Thyme Thymus polytrichus and English Stonecrop Sedum anglicum grow on rocks and very thin soils. Early spring flowers on the east side include Primrose Primula vulgaris and Bluebell Hyacinthoides non-scripta which flower at their best before the bracken reaches full size. These are followed by forests of Foxgloves Digitalis purpurea, some reaching nearly 3 metres in height, and the much smaller Red Campion Silene dioica. Towards the end of the season Goldenrod Solidago virgaurea is one of the last flowering plants to put on a show of colour and it seems to do best along the edges of the old quarries.

A typical sea cliff flora of Thrift Armeria maritima, Sea Campion Silene uniflora and Sheep’s-bit Jasione montana is found on the exposed sidelands of the island, especially around the Battery and towards the north end. At the south end, and on Rat Island Kidney Vetch Anthyllis vulneraria and Common Sorrel Rumex acetosa are more frequent, and Wild Thyme Thymus polytrichus and English Stonecrop Sedum anglicum grow on rocks and very thin soils. Early spring flowers on the east side include Primrose Primula vulgaris and Bluebell Hyacinthoides non-scripta which flower at their best before the bracken reaches full size. These are followed by forests of Foxgloves Digitalis purpurea, some reaching nearly 3 metres in height, and the much smaller Red Campion Silene dioica. Towards the end of the season Goldenrod Solidago virgaurea is one of the last flowering plants to put on a show of colour and it seems to do best along the edges of the old quarries.

Some of Lundy’s special plants, including the endemic Lundy Cabbage Coincya wrightii can easily be seen from the beach road. Balm-leaved Figwort Scrophularia scorodonia is common here and the beautiful Wood Vetch Vicia sylvatica flourishes on the steep slopes near the bottom of the road. The island’s stone walls are host to plants such as Ivy-leaved Toadflax Cymbalaria muralis and Wall Pennywort Umbilicus rupestris, and Hare’s-foot Clover Trifolium arvense grows on the top of the walls, safe from grazing animals. Fern Grass Catapodium rigidum seems to grow only on walls, along with several species of ferns, described in more detail on the Ferns page.

Some of Lundy’s special plants, including the endemic Lundy Cabbage Coincya wrightii can easily be seen from the beach road. Balm-leaved Figwort Scrophularia scorodonia is common here and the beautiful Wood Vetch Vicia sylvatica flourishes on the steep slopes near the bottom of the road. The island’s stone walls are host to plants such as Ivy-leaved Toadflax Cymbalaria muralis and Wall Pennywort Umbilicus rupestris, and Hare’s-foot Clover Trifolium arvense grows on the top of the walls, safe from grazing animals. Fern Grass Catapodium rigidum seems to grow only on walls, along with several species of ferns, described in more detail on the Ferns page.

The grassland on top of the island is typical of acid grassland in exposed areas, dominated by Purple Moor Grass Molinia caerulea in places, but bright with the flowers of Tormentil Potentilla repens in the early summer. In damp flushes the semi-parasitic Lousewort Pedicularis sylvatica can be found, often in association with Bog Pimpernel Anagallis tenella and Common Milkwort Polygala vulgaris. A good colony of Heath Spotted Orchid Dactylorhiza maculata grows in the grassland surrounding Pondsbury.

The grassland on top of the island is typical of acid grassland in exposed areas, dominated by Purple Moor Grass Molinia caerulea in places, but bright with the flowers of Tormentil Potentilla repens in the early summer. In damp flushes the semi-parasitic Lousewort Pedicularis sylvatica can be found, often in association with Bog Pimpernel Anagallis tenella and Common Milkwort Polygala vulgaris. A good colony of Heath Spotted Orchid Dactylorhiza maculata grows in the grassland surrounding Pondsbury.  In the wettest bogs, dominated by Sphagnum mosses, Common Cotton Grass Eriophorum angustifolium is very obvious in the summer and the insectivorous Sundew Drosera rotundifolia can sometimes be found. Bog Asphodel Narthecium ossifragum and Marsh St John’s Wort Hypericum elodes grow in the wettest areas and the leaves of Marsh Pennywort Hydrocotyle vulgaris form extensive patches in these wet areas, although its tiny flowers are quite hard to find. The grassland at times gives way to a dense cover of Creeping Willow Salix repens which is most obvious in the spring when the bright yellow catkins appear. Later in the season Cross-leaved Heath Erica tetralix flowers in the wetter areas.

In the wettest bogs, dominated by Sphagnum mosses, Common Cotton Grass Eriophorum angustifolium is very obvious in the summer and the insectivorous Sundew Drosera rotundifolia can sometimes be found. Bog Asphodel Narthecium ossifragum and Marsh St John’s Wort Hypericum elodes grow in the wettest areas and the leaves of Marsh Pennywort Hydrocotyle vulgaris form extensive patches in these wet areas, although its tiny flowers are quite hard to find. The grassland at times gives way to a dense cover of Creeping Willow Salix repens which is most obvious in the spring when the bright yellow catkins appear. Later in the season Cross-leaved Heath Erica tetralix flowers in the wetter areas.

Damp gravelly areas and the margins of seasonal ponds support species like Chaffweed Anagallis minima, the UK’s smallest terrestrial plant. This is now becoming scarce on the mainland but seems to do well on Lundy. Sea Storksbill Erodium maritimum is another species of gravel areas and is abundant on Lundy but much harder to find on the mainland.

On top of the island, especially around Tibbetts (Admiralty Lookout) and towards the north end, there are some fine examples of a habitat type known as maritime, or waved heath. These areas are dominated by Western Dwarf Gorse Ulex gallii which flowers late in the summer, and Ling Calluna vulgaris and Bell Heather Erica cinerea, all providing a spectacular splash of colour.

The more sheltered east side of the island supports the only trees on Lundy which grow in a few small copses in steep coombes. They are mostly hardy species, such as Sycamore Acer pseudoplatanus and Beech Fagus sylvatica, with a number of Turkey Oaks Quercis cerris scattered amongst them. Other native species include Alder Alnus glutinosa, Grey Willow Salix cinerea and Elder Sambucus nigra, and these all provide sheltered conditions for several species of plants more typical of woodland, including ferns, mosses and liverworts. Plants which favour shaded habitats are more at home here and large umbellifers such as Wild Angelica Angelica sylvestris and the invasive Alexanders Smyrnium olusatrum grow where the soil is damp. Various species of introduced conifers can be found in Millcombe, including the native Scots Pine Pinus sylvestris, but they do not thrive here.

Relics of cultivation and former habitation appear in some areas, and there are large stands of an early Narcissus cultivar Primrose Peerless Narcissus x biflora which survives near Belle Vue Cottages above the quarries.

Many interesting plants have been recorded on Lundy in the last 100 years, but some have not been seen recently. They may just have been overlooked, or possibly have vanished altogether. Any records of Lundy's Lost Plants would be most welcome.

As with other species groups we are always keen to receive records. Details of how to submit botanical records can be found here.

Text by Andrew Cleave

Although many geologists have produced papers about Lundy, the first complete study was undertaken by Dr A T J Dollar who described Lundy's granite mass as: “the denuded core of far more lofty mountains piled up during the Armorican folding ... half liquid magma pushed up into the cavities at the base of the mountainous folds of rock and solidifies. Then, as millions of years go by with their millions of seasons of rain and frost ... denude the masses ... until a time may be reached when the granite core, the solidified magma so much harder than the overlying rocks, is all that remains.”

Research since then has shown that Dollar’s assumption that the Lundy granite was of the same age as that seen on Dartmoor and Bodmin Moor was incorrect, the Lundy granite being much more recent at between 59 and 52 million years old. This means that rather than being formed during the Amorican folding (now the Varascan orongeny) they were formed as part of a period of active vulcanicity and formed part of the British Tertiary Volcanic Province (BTVP), best known in western Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Research since then has shown that Dollar’s assumption that the Lundy granite was of the same age as that seen on Dartmoor and Bodmin Moor was incorrect, the Lundy granite being much more recent at between 59 and 52 million years old. This means that rather than being formed during the Amorican folding (now the Varascan orongeny) they were formed as part of a period of active vulcanicity and formed part of the British Tertiary Volcanic Province (BTVP), best known in western Scotland and Northern Ireland.

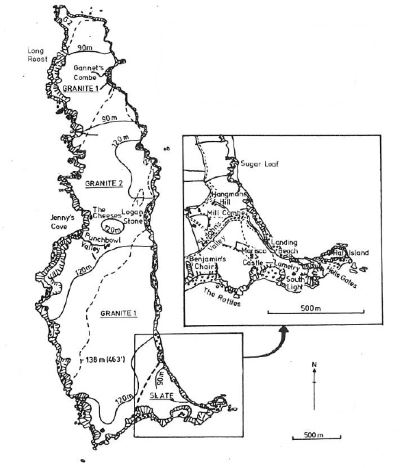

The southeast corner of Lundy is all that now remains of the overlying slates and these now join the granite in a distinct line from the Sugar Loaf to the Rattles. This slate is similar to the Morte slates of North Devon and may be called Upper Devonian. The island plateau forms a marine plane, similar to many in Southern England at the 120m (400ft) contour.

There are also numerous dykes, mostly of dolerite, that have invaded cracks in the older rocks and since formed foci for erosion. The dykes are a feature of the BTVP and are only slightly younger than the granite at 56-45 Ma. As well as the overall NW-SE trend seen throughout the BTVP, some dykes show evidence of a local centre from which they radiate. This, and the presence of a positive anomaly in the earth’s magnetic field to the west of the island suggest that there was a volcano there which probably reached the surface (although any evidence for this will have eroded away). The Lundy granite formed from the original magma chamber (possibly 10km below the surface at that time) and the dykes from later episodes of vulcanism, their different composition the result of fractional crystalisation.

Dollar classified the granite into three types: G1 which is an even-grained white orthoclase variety; G2, a variety with phenocrysts of orthoclase and quartz set in a microgranite groundmass; and G3 and G3a which are microgranites. These distinctions probably relate to the way that the granite cooled rather than being distinct types.

The plateau surface of the granite massif is almost level and bounded on all sides by steeply inclined sidelands at the base of which are vertical cliffs. The erosive activity of the many small streams that drain the surface has been minimal and virtually all the streams have developed along weaknesses in the granite or along dykes, such as those in Gannets' Combe.

There has long been discussion of the effects of glaciation on the island but the latest research has suggested that the geomorphology of Lundy can be largely interpreted as the product of glacial processes. There is widespread smooting and lineation (running WNW-ESE) of surfaces, which together with grooved whaleback forms, can be interpreted as subglacial ice moulding. There are also channels, now dry, that can also be intepreted as having formed as subglacial meltwater channels. There are large areas of eratic gravels and cobbles in the north part of the island whose composition reflects the geology of Pembrokeshire to the NW of Lundy. Their location again suggests movement by subglacial meltwater. The two main stream systems (Millcombe and Gannets' Combe) appear to have been overdeepened by meltwater following lines of geological weakness.

There has long been discussion of the effects of glaciation on the island but the latest research has suggested that the geomorphology of Lundy can be largely interpreted as the product of glacial processes. There is widespread smooting and lineation (running WNW-ESE) of surfaces, which together with grooved whaleback forms, can be interpreted as subglacial ice moulding. There are also channels, now dry, that can also be intepreted as having formed as subglacial meltwater channels. There are large areas of eratic gravels and cobbles in the north part of the island whose composition reflects the geology of Pembrokeshire to the NW of Lundy. Their location again suggests movement by subglacial meltwater. The two main stream systems (Millcombe and Gannets' Combe) appear to have been overdeepened by meltwater following lines of geological weakness.

Scientific dating has shown that the the rocks were exposed as the ice melted between 35,000 to 40,000 years ago, long before the maximum extent of glaciation was reached (the global Last Glacial Maximum, LGM, at around 26,000 to 21,000 years ago). This dating suggests that the extent and timing of glaciation is complex at the southern limits. It does show that the ice did reach this far south during the last glaciation which had been questioned before.

Following the end of the glacial, Lundy would have formed a significant hill in a wide plain where the Bristol channel now lies. As more ice melted, the sea would have risen and flooded to south and north leaving a peninsula that would have become an island at around 7500 BC. The present landscape is dominated by granite tors formed by the weathering of the granite by chemical and physical processes.

Minerals found on Lundy include copper ore which is found at the junction of the granite and slate at the south end of the island just east of Benjamin's Chair. During the mid-19th century three shafts were opened in the hope of finding workable quantities but the find was not worth commercial exploitation. A vein was also found near Long Roost and three adits were made, but the quality of ore was too poor to be worked. During the Second World War an inspector visited Lundy to see if the molybdenum ore, of which there was then a shortage, could be worked, but again the amount was not commercially viable.

Other minerals recorded are:

- Beryl - in small white-yellow columnar crystals.

- Feldspar - in white tubular crystals.

- Fluorite - crystalline and massive.

- Garnet

- Mica - in plates and hexagonal crystals.

- Rock crystal - transparent, frequently dark brown or black.

- Schorl

- China clay - formed from disintegrating feldspar, present in small; quantities but too impregnated with iron to be useful.

In the slate are are veins and strings of Gossan containing:

- Blende - sulphuret of zinc in traces.

- Towanite - copper pyrites.

- Magnetite - magnetic iron ore, found in a vein below Benjamin's Chair.

- Quartz - amorphous and crystalline is found in veins crossing the slate in every direction. This is the most abundant non-metallic mineral.

- Limestone - a seam appears on the beach and passes southeastwards through Hell's Gates. This weakness of a soluble mineral probably accounts for the separation of Rat Island from the main island.

Original text by Tony Langham, updated by Chris Webster

Fungi of all shapes and sizes can be found on Lundy, from microscopic rusts on plant leaves, delicate toadstools in a kaleidoscope of colours, puffballs, spindles, and brackets, right up to the statuesque parasols that grace the plateau in summer.

Over 850 species have so far been recorded, with new species being found every year. The main season for fungi is from late summer through to late winter, but there are always a few to be found all year round. They are most abundant a few days after wet weather, and can become very scarce in prolonged dry spells, even in the middle of autumn.

Over 850 species have so far been recorded, with new species being found every year. The main season for fungi is from late summer through to late winter, but there are always a few to be found all year round. They are most abundant a few days after wet weather, and can become very scarce in prolonged dry spells, even in the middle of autumn.

Woodland species are found not only in the woods and copses, but also associated with the ‘forest’ of Creeping Willow that grows around Pondsbury. Dung fungi are well represented due to the large number of grazing animals, but the most interesting habitat on Lundy is the areas of unimproved grassland, particularly the Airfield, and the short-grazed turf areas on the east side of the plateau.

Throughout the autumn, this grassland is dotted with the bright colours of the waxcaps, a group of fungi specific to such areas, and in decline across the country due to the fertilisation of grasslands for farming. They come in a wide range of colours including the reds of the Scarlet and Crimson Waxcaps, the yellows of the Golden and Butter Waxcaps, and also white, green, grey and even pink.

Throughout the autumn, this grassland is dotted with the bright colours of the waxcaps, a group of fungi specific to such areas, and in decline across the country due to the fertilisation of grasslands for farming. They come in a wide range of colours including the reds of the Scarlet and Crimson Waxcaps, the yellows of the Golden and Butter Waxcaps, and also white, green, grey and even pink.

At least 41 species of waxcaps have been found on Lundy, which makes it an internationally important site. The SSSI which covers most of the top of the island means that fungi should not be picked, except by permitted individuals for the purposes of identification.

It is only in the last 22 years that much effort has been put in to recording fungi on the island, but regular surveys are now carried out each autumn, along with records added by enthusiastic visitors and island staff. Forays are run for visitors whenever an LFS expert is present on the island, and the book, Lundy Fungi, by LFS members John Hedger and David George, will hopefully help more visitors become interested in this fascinating kingdom, and see more records added to the log book. There are several field guides available in the Tavern for anyone to use, plus more in the LFS library for members' use.

It is only in the last 22 years that much effort has been put in to recording fungi on the island, but regular surveys are now carried out each autumn, along with records added by enthusiastic visitors and island staff. Forays are run for visitors whenever an LFS expert is present on the island, and the book, Lundy Fungi, by LFS members John Hedger and David George, will hopefully help more visitors become interested in this fascinating kingdom, and see more records added to the log book. There are several field guides available in the Tavern for anyone to use, plus more in the LFS library for members' use.

The definitive list of fungi found on Lundy, including species discovered since the publication of the book, can be viewed here. There are also lists of chromists and protists.

Text by Mandy Dee

More articles on Lundy fungi

As is often the case with small islands Lundy has few naturally occurring species of land mammal, although the island's history is rich with examples of deliberate and accidental introductions, not all equally successful.

Native species

The only indigenous Lundy mammal is the Pygmy Shrew Sorex minutus. These tiny insectivores can be seen in and around the properties but also survive in the natural landscape. In recent years thay have been reported from most properties in and around the village but are not dependent upon human habitation having been seen at Halfway Wall, the Terraces and as far north as North Light.

Bats are occasionally observed on Lundy and are usually assumed to be one of the native pipistrelle species; Common Pipistrelle Pipistrellus pipistrellus or Soprano Pipistrelle P. pygmaeus. A passive detector study by Geoff Billington during 2014 confirmed the presence of these two pipistrelle species as well as Greater Horseshoe Bats Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, in relatively high numbers in May. More unusual species detected during this study included the recently discovered Alcathoe Bat Myotis alcathoe, Nathusius Pipistrelle Pipistrellus nathusii and Barbastelle Barbastella barbastellus. Two species not considered resident in the UK were detected; Kuhl’s pipistrelle Pipistrellus kuhlii and Savi’s Pipistrelle Pipistrellus savii. Other species detected in low numbers included Noctule Nyctalus noctula, Long-eared Bat Plecotus sp. and Myotis species which were not identified to species but one was considered to be a Whiskered or Brandt’s Bat Myotis mystacinus / brandtii.

Introduced species

Rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus are believed to have been brought to Britain after the Norman conquest and there are written records that they were being taken from Lundy for meat and fur as early as 1183. In the early twentieth century many thousands were killed on Lundy each year, with nearly 11,000 believed to have been taken in 1929 alone. It was still considerd to be 'abundant' during an LFS mammal survey in 1953.

The flea-borne disease myxomatosis first appeared in the Lundy Rabbit population in 1983 more than 25 years after it became prevalent on the nearby mainland and probably through deliberate introduction. Following the initial population collapse numbers have fluctated widely with major outbreaks in 1992 and 1996. As recently as 2013 there were reported to be at least 1000 Rabbits still on the island, but since then numbers have plummeted, with Viral Hemorrhagic Disease (VHD) suspected.

Soay Sheep Ovus aries of St Kilda are the most primitive domestic sheep in Europe, resembling the original wild species and the domesticated Neolithic sheep which were first brought to Britain in about 5000 BC.

Soay Sheep Ovus aries of St Kilda are the most primitive domestic sheep in Europe, resembling the original wild species and the domesticated Neolithic sheep which were first brought to Britain in about 5000 BC.

Soays were introduced to Lundy in 1942, with additions in 1944 bringing the flock to one ram and seven ewes. By 1953 there were 70 or 80 and in 1995 an island-wide survey counted 278. The Lundy Soays now constitute the third largest closed flock of this breed existing in a feral state anywhere in the world and the largest away from St Kilda. Their grazing is of value in assisting in the maintenance of the semi-natural grasslands and heathlands in the northern parts of the island. The 2010 terrestrial management plan recommended that the population be maintained at 120-150 breeding ewes plus followers providing around 30 lambs for slaughter each year. Recent assessments that put the size of the flock at over 300 animals.

Seven Sika Deer Cervus nippon were introduced to Lundy in 1927 and increased in numbers, despite regular culling, to around 90 individuals in 1961. Before the Rhododendron thickets were cleared from the east sidelands, Sika would shelter there during the day and would only be easy to see in the early morning or evening. Nowadays they are more obvious but relatively few counts are reported and members are encouraged to enter these in the LFS logbook, held in the Marisco Tavern. The 2010 terrestrial management plan recommended that a population of 30 mature hinds and 10 mature stags would form a sustainable population, without adversely impacting the the semi-natural vegetation communities, with the proviso that these targets are regularly reviewed. Culling is still carried out to manage the population size and provide produce for the tavern kitchen, although numbers are typically in excess of the target. In 2022 the post-breeding population was estimated to be in excess of 130 individuals.

Seven Sika Deer Cervus nippon were introduced to Lundy in 1927 and increased in numbers, despite regular culling, to around 90 individuals in 1961. Before the Rhododendron thickets were cleared from the east sidelands, Sika would shelter there during the day and would only be easy to see in the early morning or evening. Nowadays they are more obvious but relatively few counts are reported and members are encouraged to enter these in the LFS logbook, held in the Marisco Tavern. The 2010 terrestrial management plan recommended that a population of 30 mature hinds and 10 mature stags would form a sustainable population, without adversely impacting the the semi-natural vegetation communities, with the proviso that these targets are regularly reviewed. Culling is still carried out to manage the population size and provide produce for the tavern kitchen, although numbers are typically in excess of the target. In 2022 the post-breeding population was estimated to be in excess of 130 individuals.

Goats Capra hircus have probably existed on Lundy since the time of its earliest human inhabitants, and it is likely that some of these would have escaped. Further introductions occurred in 1926 and subsequently. Today the population varies between 30 and 50 and all have the typical appearance of wild goats; long-haired with horns. Numbers are controlled to keep the population stable and they are actively discouraged south of Quarter Wall to minimise damage to the Lundy Cabbage and other key plant communities.

Goats Capra hircus have probably existed on Lundy since the time of its earliest human inhabitants, and it is likely that some of these would have escaped. Further introductions occurred in 1926 and subsequently. Today the population varies between 30 and 50 and all have the typical appearance of wild goats; long-haired with horns. Numbers are controlled to keep the population stable and they are actively discouraged south of Quarter Wall to minimise damage to the Lundy Cabbage and other key plant communities.

Extinct introduced species

The Ship Rat Rattus rattus and Brown Rat Rattus norvegicus are both originally of Asiatic origin. The former is thought to have been present in Britain since at least the twelfth century and maybe since Roman times, but the latter arrived around 1720. It is not clear when either species reached Lundy or by what means. They could have travelled in baggage or supplies, or desserted one of the many ships that have been wrecked along the Lundy coastline. By 1877 Brown Rats were numerous and the Ship Rat was in decline.

With numbers of Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus and Puffin Fratercula arctica in strong decline and with rats strongly implicated in the low productivity of these burrow-nesting seabirds on Lundy, the Seabird Recovery Project was initiated in 2002. Its primary aim was to increase the numbers and breeding success of these two species by eradicating rats from the island. This was a difficult and controversial decision particularly in relation to the Ship Rat which many considered to be “Britain’s rarest mammal”. After 17 months of poisoning with baited traps and a further 21 months of monitoring, Lundy was declared rat free in 2006. In repsonse, number of Manx Shearwaters and Puffins have increased and Manx Shearwaters raised on Lundy have been shown to be returning to the island to breed themselves.

Fallow Deer Dama dama and Red Deer Cervus elaphus were introduced to Lundy by Martin Coles Harman. Both established sizeable herds but over-culling is thought to have reduced the numbers below a sustainable level. Fallow Deer were last recorded in 1954 and Red Deer in 1962.

Unsuccessful attempts were also made to introduce Brown Hare Lepus europaeus, Red-necked Wallaby Macropus rufogriseus. Red Squirrel Scurius vulgaris, were introduced on several occasions but were extinct by 1930.

Domestic stock

In 1928 Martin Coles Harman introduced a herd of fifty ponies to the island in an attempt to establish a new breed of pony. This initial herd mainly consisted of New Forest ponies and Welsh Mountain ponies. The Lundy Pony is an officially recognised breed, with a herd of around twenty ponies being kept on the island. They can usually be found in the Pondsbury area between Quarterwall and Halfway Wall.

The working farm on Lundy includes a flock of Domestic Sheep comprising a mixture of Texel and Cheviot breeds and numbering 300 lambing ewes. A herd of Highland Cattle was introduced in 2012 as part of the island’s conservation programme, to assist with the control of rough foliage such as Purple Moor Grass (Molinia sp.) to increase the vegetation diversity. There are currently nine steers. In recent years there has also been a small herd of Gloucester Old Spot Pigs, but there are none on the island at the moment.

Text by Chris Dee, 2018; updated 2023

There are no articles in this category. If subcategories display on this page, they may have articles.

Latest news

Looking for fungi on Lundy during Lockdown by Puffin Post

Frustrated by not being able to visit the island in November for his regular survey of Lundy fungi, John Hedger has found a novel way of continuing his studies. With the help of Rosie Ellis, 'Puffin Post' and Royal Mail, he has identified 30 species found on herbivore dung, including 22 new to Lundy. Read more ...

Discover Lundy 2021 cancelled

The restriction on shared occupation of rental properties that will be in place at the time of the planned Discover Lundy week in May has persuaded us that there is no alternative to cancelling the event. The committee are sorry that many members will be disappointed by this sad, but unavoidable, decision. The AGM which was planned to take place on the island on 15 May has also been postponed and alternative arrangements will be announced when we have more details.

Discovering Lundy now published

The new issue of the LFS bulletin 'Discovering Lundy' has been posted out to members today, so look out for your copy dropping through your letterbox next week!